Katie Burk, MPH, is the viral hepatitis coordinator at the San Francisco Department of Public Health and is on the coordinating committee of End Hep C SF. In this Hep Story, she reflects on adopting the goal of hepatitis C elimination.*

On July 28, 2016, San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) Director Barbara Garcia stood at a podium on the steps of San Francisco City Hall in front of news cameras, reporters and a large crowd of hepatitis advocates and declared that San Francisco is the first city in the United States to set the goal of hepatitis C elimination. Annie Luetkemeyer, MD, an infectious disease physician and researcher who treats hepatitis C virus (HCV), later stood at that same podium and emphasized this rare opportunity to eliminate an infectious disease. Hepatitis C can be tackled by highly effective medications that cure most people, putting its elimination within our reach. We no longer have to debate about whether everyone living with hepatitis C would benefit from treatment, Annie explained—we have data demonstrating that all those who are cured can benefit, regardless of how much liver damage they may have. However, we can’t simply treat our way out of the hepatitis C epidemic. Widespread treatment must be paired with testing so that all San Franciscans know their status and become educated about how to prevent infection and reinfection after cure. Our job is to figure out how to put these tools to work and to make this potential for elimination a reality.

I think it’s fair to say that it was a proud moment for the 70-plus participants of End Hep C SF. We were making a bold statement and celebrating our leadership, vision and commitment to do more to end hepatitis C in San Francisco.

In reflecting on the planning that got us to this point, I admit that when Annie first approached me about a hepatitis C initiative, I was hesitant to take on elimination as our goal. I reasoned that it’s one thing for a clinician to imagine the elimination of hepatitis C—you’d have a good start if you could treat everyone in your clinic population and get the other doctors in San Francisco to do the same. Researchers, too, can envision hepatitis C elimination in a specific way. They offer thought exercises and models that predict reductions in prevalence relative to the scale-up of treatment and other prevention methods. This is vital and fascinating work, but on my more cynical days, it can feel distant from what we see happening on the ground for people living with hepatitis C who are disenfranchised or underserved.

As a viral hepatitis coordinator, I have a different perspective about hepatitis C elimination as it relates to program administration. Like Annie, I am intimately acquainted with the enormity of the problem and the way it interplays with seemingly intractable social issues like homelessness, drug use and stigma. My programmatic-specific perspective can get overwhelmed by the relative lack of resources we have nationally to address hepatitis C across the continuum of care. In the United States, there is woefully inadequate funding for hepatitis C prevention, testing, care and treatment. The National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) argues that we need at least $170 million dollars in federal funding to adequately address viral hepatitis. The current budget for the Division of Viral Hepatitis at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is $34 million. (https://www.nastad.org/domestic/viral-hepatitis/hepatitis-appropriations-partnership) I was concerned that by setting such an ambitious agenda we could appear out of touch with these realities.

But in talking more with Annie and colleagues, I couldn’t help but ask myself some questions. What would it look like if we had an army of providers treating hepatitis C in San Francisco and they could all work under a shared vision to develop creative and aggressive interventions to get the most complex patients treated on the patients’ terms? What if both the public and private medical sectors shared best practices with each other to develop primary care capacity to treat hepatitis C, partnering with behavioral health services and creating quality improvement measures? What happens when every methadone counselor and syringe access and homeless shelter staff person in San Francisco comprehends his or her respective role as encompassing hepatitis C prevention, testing and linkage-to-care interventions? And what possibilities lie in combining the brainpower of our brilliant epidemiologists and researchers so that we can understand the burden of hepatitis C in more nuanced ways and develop better interventions to reach those living with the virus who remain undiagnosed or untreated?

I don’t think any city or health department can answer the questions above because none of us have scaled up services to this extent. We’ve been hindered by lack of funding, the fractured nature of our health care system and silos in behavioral health and prevention services. I now believe that in the process of trying to answer the questions above, of making incremental changes that continually increase the scope of our hepatitis C interventions, we will be well on our way to eliminating hep C in San Francisco.

People have asked me how we managed to get all the End Hep C SF partners to buy in, but that part actually wasn’t that difficult. Annie and I, along with Kelly Eagen, MD, the SFDPH’s clinical lead on primary-care-based hepatitis C treatment, did a little outreach and made some calls. It turns out that epidemiologists, clinicians, and harm reduction and substance use treatment program staff across the city wanted to answer those questions too. No arm-twisting was required—they were more than willing to show up with no incentives beyond their desire to see a San Francisco without hepatitis C. As a collective impact initiative, the job of End Hep C SF is to provide the space and structure for the brainstorming, planning, fundraising and harnessing of our collective wisdom and resources to continually move us closer to our vision.

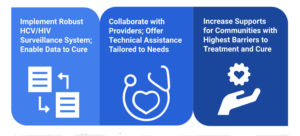

It’s been about two years since the initial conversations that led to the creation of End Hep C SF. In that time, we have developed a multidisciplinary coordinating committee, four functioning working groups and an executive advisory committee. We have, as I mentioned, more than 100 people participating in various ways, including people affected by hepatitis C. At the time of writing, we have commitments from 32 community-based organizations, patient advocacy groups, public health clinics, private medical practices, pharmacies and health plans to be partners in this effort. We have produced a strategic plan, launched a website, disseminated a nationally recognized HCV education campaign, increased community-based HCV testing by almost 20 percent, trained dozens of providers to treat HCV and created HCV treatment access opportunities in primary care, drug treatment programs, jails and homeless service organizations.

And we’ve still got a lot to do. We need to figure out how to disrupt San Francisco’s high hepatitis C incidence rate, to cure all San Franciscans living with hepatitis C, to scale up prevention, testing and linkage services and to raise funds to carry out all these plans. But I no longer doubt that it’s possible to do everything we’re envisioning. A multidisciplinary and growing collaborative of 70 passionate, committed hepatitis C experts also believe we can #EndHepCSF!

*This is a personal reflection piece. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the City and County of San Francisco; nor does mention of the San Francisco Department of Public Health imply its endorsement.

What three adjectives best describe you?

Friendly, driven, goofy.

What is your greatest achievement?

I will risk an embarrassing level of corniness and say my family.

What is your greatest regret?

I’m not big on regrets and try to understand mistakes as learning opportunities. But I probably should have done student loans differently.

What keeps you up at night?

The U.S. is in a very dark and dangerous time socially and politically. I have lost more than a little sleep thinking about it.

If you could change one thing about living with viral hepatitis, what would it be?

Take away the stigma and shame that are often associated with viral hepatitis. And make the hepatitis C cure much more easily and quickly available for everyone living with it.

What is the best advice you ever received?

Be open to career opportunities and changes.

What person in the viral hepatitis community do you most admire?

This is tough because there are so many. I am a huge fan of End Hep C SF partners Orlando Chavez who works at Glide Foundation and Pauli Gray who works at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. They are both amazing harm reductionists who use their experiences as [cured] HCV survivors to help them connect with and advocate for homeless folks and drug users living with HCV so they can be treated and cured. I also get to work with Rachel McLean at the California Department of Public Health who is an awesome model of how to be a radical bureaucrat.

If you had to evacuate your house immediately, what is the one thing you would grab on the way out?

My kid!

If you could be any animal, what would you be? And why?

A dog because they are just love, fun and naps all day, every day.